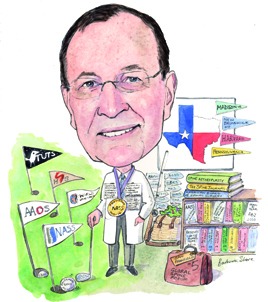

Initially intending to do a PhD in psychology, William C Watters III (clinical associate professor, Baylor College of Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Houston, USA) switched to medicine when he realised he wanted greater exposure to clinical problems and eventually found that the most intellectually and technically challenging problems involved the spine; therefore, he chose to subspecialise in spinal surgery and is now the current president of the North American Spine Society (NASS).

Why did you decide to become a doctor and why, in particular, did you decide to specialise in orthopaedic surgery?

As an undergraduate I majored in psychology and graduated into a PhD programme in that area. While this was interesting work, it lacked intense exposure to clinical problems. Thus I decided to stop with my Master’s degree and go to medical school. My intent was to become a psychiatrist. Being a medical student at Harvard was like being a kid in a candy store—everything was interesting! I graduated and did a residency in internal medicine with the intent to subspecialise in a medical specialty, not psychiatry anymore. However, my internal medicine training proved to me that I really desired to be a surgical interventionist as opposed to a medical physician. And of all the surgeons I had come to know, the orthopaedists seemed to be the happiest, so that was for me! Once involved in my orthopaedic training, the most interesting problems to me and the most intellectually and technically challenging problems involved the spine. My background in both psychology and internal medicine has actually served me well in looking at spinal problems from more than just a surgical viewpoint.

Who have been your career mentors and what influence did they have on your career?

My early experience in orthopaedic residency at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia was influenced greatly by two mentors: Richard Rothman and Henry Sherk. Both were founding members of the Cervical Spine Research Society and both were early contributors to the development of NASS. Dr Rothman had a large spinal practice and wrote extensively in spine. He was an innovative, systematic thinker who was a technical master. Dr Sherk was equally talented as a surgeon and a prolific writer and my first partner. Both set standards for me as a practitioner/scientist that I continue to try to emulate today.

I have been greatly influenced in many different ways in my practice here in Houston by Michael Heggeness, Charlie Reitman, Steven Esses and Stan Gertsbein. All have played a very active role in the development and growth of NASS with Dr Heggeness being a recent past president.

During your career, what do you think have been the most important developments in spinal surgery?

One of the most important developments during my career in spinal care has been the improved clarity that MRI has brought to the diagnosis of spinal pathology. This clearly is still a work in progress, but each year brings further improvements in our ability to diagnose spinal conditions and accurately plan efficient surgical interventions when indicated. The introduction and refinement of the safe use of internal fixation for the entire spine has been tremendously important, particularly in the areas of deformity, trauma and tumours of the spine and now its evolution into minimally invasive applications may prove equally important.

Finally, I would argue that the introduction of evidence-based medicine into the paradigms of spinal care is very important and will markedly improve our ability to use all of these technologies more appropriately, efficiently and economically in the care of spinal disease to improve treatment outcomes.

Spinal surgery is a subspecialty of orthopaedic surgery and neurosurgery, but do you think it will become a specialty unto itself?

One would think the answer is an easy “yes”. But at this point in time, the gods seem aligned against this. The American Board of Spine surgery, a small but dedicated group of multispecialty spinal surgeons, has been chasing this Holy Grail for over a decade to no good effect. First of all, the American Board of Medical Specialties has set the bar very high to add any additional specialty to its currently recognised list of 24. More importantly neither the American Board of Orthopedic Surgery nor the American Board of Neurosurgery and their associated societies have shown any interest in a specialty (or subspecialty) of spinal surgery .

Of the work you have been involved with, what are you most proud of and why?

I am most proud of the role I have played as the guidelines chair and then the research council chair at the NASS and as the first chair of the guidelines oversight committee at the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) in bringing the principles of evidence-based medicine to both societies. Both societies have embraced these principles and have become leaders in promoting the importance of evidence in the decision making in musculoskeletal care.

What are your current research interests?

Currently, I am most interested in further improving the decision processes in diagnosis and treatment of spinal conditions through the use of guideline derivatives. Evidence-based guidelines rely on the existing clinical literature and applying rules of evidence to this literature to make recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. These recommendations are then rated as to their strength (how certain the recommendation is to be valid) based on how strong (reproducible) the literature is. Unfortunately, the spinal literature, until very recently, has been lacking in high value, quality research on patient outcomes. Thus many of the evidence-based guidelines fall short on strong recommendations because the literature base is weak. To help compensate for this, several techniques have been developed to take the systematic literature reviews used for guideline development and to address the “gaps” in that literature with those of systematically developed expert opinion (this is a guideline derivative). One example of this is that of appropriate use criteria, a technique developed by the RAND Corporation. Whereas evidence-based guidelines tell you what you should do (if high-level literature exists to tell you), appropriate use criteria tell you what is appropriate to do for a condition when that type -of high-level evidence is not available. We have been -developing these appropriate use criteria at both NASS and the AAOS along with some novel cross-platform -IT apps that are proving very useful evidence-based clinical tools for the practising surgeons.

What do you think will be the next big development in spinal surgery?

From a technological standpoint, I do not see any “breakout” technologies for actual surgical intervention in the near future, but I do feel surgeons will be successful in continuing to develop increasingly effective minimally invasive techniques for the majority of spinal procedures. This will greatly decrease the morbidity of these procedures and contribute to decreasing infection rates and increasing speed of recuperation. Further developments of robotic stereotaxis could well contribute to this practice. Advances in tissue engineering and genetic engineering hold great promise in the longer run to correct spinal pathology especially that related to the degenerative process, and further diminish the invasiveness of spinal surgery. It is important for spinal surgeons to maintain awareness and involvement in these biologic areas so that they can exert a degree of ownership of these technologies.

As the 2013–14 president of the NASS, what do you think have been the key achievements during the past year?

There have been several key achievements for NASS during this period. We have brought to fruition a series of evidence-based coverage recommendations covering a multitude of common diagnostic and treatment procedures in spinal care. These documents are another kind of guideline derivative that are created from both systematic reviews of the literature combined with a strong input from some of the world’s experts on the topics covered and made available to our membership to help them argue for appropriate coverage of care required by their patients. Our spinal care registry, the first ever to cover the spectrum of spinal care including non-operative and operative care, will begin pilot testing in this period and will be an important addition to evaluation of the care we give patients. A distinction programme is nearing the end of its development and will be available to our members to further highlight their expertise as a spinal care specialist. Also, ground work is being laid to develop a foundation to promote spinal health. All these efforts can be summarised by saying that NASS has continued its efforts to use ethical and professional principles in advocating for the provision and coverage of quality spinal care.

What do you think the highlights of this year’s meeting (12–15 November, San Francisco, USA) will be?

We are going to have a very exciting meeting in San Francisco this year. On the scientific side, we have had more than 1,000 abstract submissions reviewed this year and excellent papers will be presented in all fields of spinal care. In addition, the top 21 abstracts will be presented at various points throughout the meeting to more broadly highlight these excellent works. The programme will have a strong clinical focus this year highlighting practical content for managing the current and future realities of practice. There will be a variety of sessions on healthcare models and reimbursement and on implementing the Accountable Care Act in spinal care.

We will have our fifth Annual Global Spine Forum featuring international organisations discussing spine care around the world. Furthermore, we have responded to membership’s requests for additional networking opportunities and this year’s programme will include several events to give attendees a chance to meet with others with similar interests or from similar areas of the county.

You have an interest in the psychology of human behaviour and learning. Has this interest helped you to manage patients with spinal conditions?

Experiencing spinal pain, even from conditions that are not life-threatening or likely to produce prolonged disability, can be very confusing and scary to a patient. First-time visits to a physician for acute spinal pain are often marked by anxiety and fear. The patient does not know what is wrong; what has happened; if it will get better; if it will get worse; if there will be neurological decline; or it will threaten his or her life or work.

On the other hand, patients who present with chronic pain from a spinal condition looking for hope and help to resolve their pain and dysfunction are frequently depressed. The depression may be a result of the constant spinal pain itself, it may be worsened by medications they are on or it may be from an entirely unrelated source but contributing to the patient’s dysfunction. In others words, spinal conditions, more than almost any other medical condition I have had experience with present with very important emotional overtones, and often in very complex psychological contexts. The spinal community is becoming increasing aware of this and the effects the patient’s psychological state can have on treatment outcomes. As such I do feel my additional training in human behaviours has been an adjunct to managing these patients and I think there should probably be more emphasis on this aspect of spinal care in our training programmes.

Which case has taught you the most about the management of spinal conditions?

One of my mentors in training used to repeatedly point out that “Good judgment comes from experience. And unfortunately, experience comes from bad judgment!” No truer words were ever spoken. We learn the most from difficult cases and unexpected consequences. Earlier in my career I almost lost a healthy young woman during a routine but difficult multilevel-fusion when she developed disseminated intravascular coagulation. We were late in making the diagnosis during the surgery and she lost over 12 litres of blood. Her postoperative care required a week in the intensive care unit and was marked by physical debilitation and a profound depression until she fully recuperated. Providing care for her through the surgery and the whole recuperation was one of the most demanding and educating experiences of my career. It demonstrated to me that the case is not over when the patient leaves the operating room but demands care and concern through the entire healing process. She and our doctor-patient relationship survived and her eventual recuperation was full. She actually wrote a very caring and insightful article about her experience for a non-medical journal.

Outside of medicine, what are your hobbies and interests?

My wife and I have had an amazing experience raising two boys and are fortunate to have both living relatively close to us as they develop their careers and start families of their own. I enjoy international travel a great deal and play golf (not enough) and go fly fishing (again, not enough) for relaxation. Reading and music are constant companions.

Fact File

Appointments

2008–present -Clinical professor, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Texas Medical Branch Galveston, USA

2003–present Associate professor, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, USA

1982–2002 Clinical assistant professor, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, USA

Postgraduate training

– -Orthopedic surgical resident

– -University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

– -Surgical resident

– -Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

– -Medical resident

– -Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

– -Medical intern

– -Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

Boards and committees

2013–14 -President, NASS

2012 Co-chairman AMA PCPI Low Back Pain Measure Development work group

2011–present -Clinical and Scientific Advisory Board, World Spine Care Project

2011–13 -Chair of the AAOS Appropriate Use Criteria Committee

2011–13 -Co-Chair of the AAOS and American Dental Association Workgroup on an evidence-based guideline for the prophylaxis of patients with orthopedic implants undergoing dental procedures

2010–present -Clinical team, surgery, World Spine Care Project