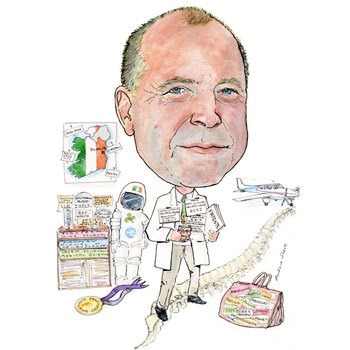

Ciaran Bolger, professor of Clinical Neuroscience at Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, Ireland, is the immediate past president of Eurospine. He talked to Spinal News International about his career in spinal surgery and becoming the first Irish astronaut.

Why did you choose medicine as a career and why did you choose to specialise in spinal surgery?

I chose medicine as a career when I was very young—the earliest memory I have is people asking me as a small child what I wanted to be when I grew up and me saying that I wanted to be a doctor. I have no idea why I decided to be a doctor at such an early age. I have no family connections in medicine whatsoever and I have no history of having family friends being involved in medicine, so I must have been influenced by something I saw on television etc.

When it comes to spinal surgery, my first interest was in neurosurgery. However during my neurosurgery training, in the early 1990s, I felt that spinal surgery was really the “Cinderella” of neurosurgery and that there were many aspects of spinal surgery that we did not have expertise in. Therefore, I arranged to do an orthopaedic fellowship to increase my knowledge and found that being trained both as a neurosurgeon and as an orthopaedic surgeon in terms of spinal surgery gave me a lot of advantages in dealing with the problems that I was coming across. When I finished my training as a neurosurgeon in 1994, spinal surgery was beginning to take off. It was really an exciting area to be involved in at that time and attracted me for that reason.

Who has inspired you in your career and why?

So many people have inspired me over the years. From my parents through to teachers in school through to lecturers in university who influenced my career and got me interested in neuroscience and eventually neurosurgery.

From my spinal career point of view, I have been very influenced by Gordon Findlay in Liverpool, who was my teacher and introduced me to more complex spinal surgery as a neurosurgery trainee. After that, I travelled to Adelaide where I did an orthopaedic spinal fellowship and I was immensely influenced by the people there. Particularly, of course, Robert Fraser, who is the head of the unit but also David Hall and Chris Cane, who were his two orthopaedic colleagues specialising in spinal surgery. There was also Professor Nigel Jones, who was the neurosurgeon in Adelaide specialising in spinal surgery. Between them, they really influenced my outlook on spinal pathology and how it should be dealt with. They taught me surgical approaches that I had not known existed and taught me to be analytical about what I was doing with patients and to always assess outcomes. I think collectively their enthusiasm for the subject and their enthusiasm in teaching me was something that had an immense effect on me and really solidified my decision to specialise in spinal surgery.

What have the most important developments in spinal surgery been during your career?

I have been fortunate to work in the areas of spinal surgery that have had a period of immense growth and discovery. For example, the adaptation of fixation systems and the development of screws and rod systems for all of the spine, including a cervical-plating system that allowed us to stabilise patients much more regularly without prolonged external supports. I was immensely influenced by the development of computer-aided surgery and managed to be involved in developing this technology right from the very beginning. From using early systems that had been primarily designed for cranial neurosurgery and adapting them to the spine, right through to the present day and the use of the “O”-arm technology to allow on-table imaging, which have been of immense benefit to managing patients.

Also, the developments in patient assessment outcomes scales and the enhancement of our understanding of psychological roles as they apply to our patients have been immense developments in our understanding of the patients and pathologies that we deal with, and are as equally important as the technological developments in relation to the surgery we do itself.

You have worked in Australia, the UK, and Ireland. What were the differences between these countries in terms of their approach to spinal surgery and what were their similarities?

I have to say for the most part, the approach to spinal surgery in all of these countries has been broadly similar. Surgeons in the UK have tended to be more conservative and less inclined to interfere operatively than the surgeons in Australia, but the Australian experience would be a lot closer to the UK experience than it would be, for example, to the situation in the USA where there is a much higher rate of operative intervention. In Ireland, we fall somewhere between the UK and Australia in terms of aggressiveness in relation to surgery.

In all three, during my career, there has been a rapid expansion in the number of neurosurgeons who are involved in instrumented spinal surgery and in more complex reconstruction.

In terms of the patient experience, the main difference is that access to medical services and to treatment would seem to be a lot more readily available in Australia than it is in either the UK or Ireland—particularly, for more minor problems such as disc prolapses etc. In Ireland, there is an inordinate delay in being able to treat patients with so called more minor spinal pathologies; however, these more minor spinal pathologies have a large impact economically.

Patients with sciatica, a relatively easy condition to treat, are often the younger, more economically productive patients and yet their treatment can be delayed for many months, delaying their recovery and return to gainful employment. Typically in Ireland, a public healthcare patient may wait a year to have a disc operation whereas in Australia, patients had ready access to treatment and ready access to surgery should they need it. It is sometime since I worked in the UK but certainly at the time I did work there, the situation was very similar to Ireland in that there were a lot of delays for more elective procedures.

During your time as president of Eurospine, one of your goals was to make the society more professional. What steps did you take to try to achieve this goal?

The first thing was that I signed contracts of employment with the people involved in the administrative side of the society. Prior to this, the engagement with the staff had been very much on an ad hoc remuneration basis and they really worked as independent contractors. I managed to negotiate contracts and bring them in as employees, which was better from their point of view and also from the society’s point of view. I also revamped the way we present our annual report. Previously, the annual report really consisted of a booklet with a list of members. It is now a much more modern document with end-of-year statements regarding our finances and reports from each of the chairs of the various subcommittees of the society, which means that the members and other interested parties can see exactly what is going on in the society and where we our spending our money etc. I also worked extensively, with the help of Gerard Vanacker, who is the chief executive officer of the Eurospine foundation, for the development of a strategic plan for the society to shape and identify our goals for the future. Hopefully this strategic plan will be finalised this year and be presented to the members for approval. Eurospine has grown enormously during the years that I have been secretary and president. We need to have a more professional focus, administration and management systems.

What was appropriate for an organisation with an annual attendance at meetings of a few hundred is no longer suitable when our meetings have an annual attendance approaching 4,000!

Of the spinal surgery products you have been involved in developing, which product are you most proud of and why?

Each of the products I have been involved in developing have a special place and memory for me because of the achievement and the work that went into them, and I am really proud of all of them.

The one that has been most successful and the one that I am most proud of is the PediGuard (SpineGuard) device, which detects perforation in bone when implanting pedicle screws. I developed this with Mr Maurice Bourlion and Mr Alain Vanquaethem, two engineers who were really responsible for most of the technological achievements. I am proud of it because it took an enormous amount of effort and development in terms of prototypes and overcoming technical problems and trials of different versions. After all of the setbacks and work involved, it was tremendous to finally develop a useful and commercially viable device that is growing exponentially in popularity. I am also proud of it because it is a product that is directly aimed at improving the lives of surgeons and patients, and it is a device that is directly related to the safety of patients.

What are the three spinal surgery questions that need answering?

- While we know that most degenerative diseases and low back pain can be explained by genetic factors, I would like to see a better understanding of what exactly the environmental triggers are in association with these genetic factors.

- I would like to see a treatment, which I do not think at the end of the day would probably be surgical, for intramedullary spinal cord tumours, particularly astrocytomas. These are very difficult tumours to treat and they are usually not completely excised with surgery. I would like to see some development, perhaps of immunotherapy or chemotherapy, which would help us deal with these particular tumours that are devastating for the patients and their families.

- What is the best treatment for low back pain? This is a question that still perplexes us and one that we still do not have the full answer to.

What are your current areas of research?

I am involved in many areas of research; however, nowadays, I have far less involvement in more basic research. Most of my investigation is related to the development of minimally invasive techniques of accessing the spine from top to bottom. I am also currently running a trial looking at a bone substitute, which hopefully turn out to be osteoinductive.

At a broader level, I continue to have an interest in the brain stem, which for most spinal surgeons is the bit of the body on top of the actual spine. It is an intriguing area and I am still doing quite a bit of work in relation to monitoring of brain stem function.

What recent spinal paper have you found the most interesting and why?

The recent papers I have found most interesting really are a series of papers from the SPORT (Spinal Patients Outcome Research Trial) group. While that particular study has come in for a lot of criticism, it has produced a lot of very interesting data in relation to the management of patients, particularly with spinal stenosis. The most interesting feature to emerge recently is the fact that decompression of the canal contents can, in fact, produce an improvement in back pain itself, which is something that we preached for a long time was not the case.

You are the recipient of several awards for your work in spinal surgery. Which award was the biggest honour and why?

I think the biggest award was the Presidential Design Award from the president of Singapore for the PediGuard. This was a great honour as it is a large international award, covering not only medicine but all areas of technological development. I think to receive this award was a tremendous recognition of the work done by everyone involved in the development of this device.

Do you think social networking, such as Twitter, has a role in the spinal community and if so, what role?

I think social networking could have a role for the spinal community, but I am not sure that the format of something like Twitter would be very useful. Twitter tends to be a more immediate short comment kind of communication, whereas I suspect that the networking that we could associate with the spinal community would be far more along the lines of a longer interaction with transfer of images and files and development of an online community where one could get advice and show difficult cases etc. I think such communities will emerge in time on perhaps on Facebook, rather than Twitter.

What are your hobbies outside of medicine?

Outside of medicine my major interest is in flying. I fly a twin-engine Beech Baron Pressurised Airplane. It is a beautiful aeroplane, which allows me to fly at 25,000 feet around Europe above the weather and gets me from place to place particularly for all the different European meetings that I attend. It was very useful during my year as president at Eurospine.

I have an interest in space travel and technology, and I was in fact the official Irish astronaut to the European Space Agency in the early 90s. Although I never got to actually fly in space, I did get to do the full selection process that involved G-Force testing in a centrifuge with lots of interesting experiences related to that.

Unfortunately, as I say, I never got to go into space and I think I am past the stage where I would be a reasonable candidate now—although the experience of John Glenn [who went into space aged 77] in the USA gives me hope that maybe by the time I am 70, it will be something I can return to!

How did you become the first official Irish astronaut?

I became the official Irish astronaut following a selection process in Ireland related to a recruitment drive from the European Space Agency in the early 90s. However, Ireland contributes very little to the European Space Agency and I do not think it was any surprise that an Irish astronaut has yet to be selected to actually go into space. My family, however, are firmly convinced that I have always been a “space cadet” and while I never made it to the moon I have made it to Beaumont Hospital in Dublin, which sometimes resembles a lunar landscape!

Fact File

Appointments (selected)

2002–present Professor of Clinical Neuroscience, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

2002–present Head of Department, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

2001–present Director of Research Development, National Neurosurgery Unit, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

2000–present Consultant neurosurgeon, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

1996–2000 Consultant neurosurgeon, Frenchay Hospital, Bristol, UK

1995 Consultant Neurosurgeon, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide. South Australia

Qualifications

1995 SAC Accreditation Neurosurgery, Royal College of Surgeons

1995 FRCSI (SN) Intercollegiate, Royal College of Surgeons

1994 PhD, Trinity College Dublin

1991 FRCSI, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland

1987 MB BCh BAO, Trinity College Dublin

1984 BA (mod) Neurophysiology,Trinity College Dublin

Prizes

2000 Royal Academy Medicine Ireland

1999 Intensive Care Society, London ISSLS, Hawaii

1987 Gold Medal Final MB Adelaide Hospital

1985 Gold Medal, Biological Society

1984 Gold Medal Final BSc, Trinity College Dublin

Societies

- President (2011), Eurospine (Spine Society of Europe)

- Representative of SBNS to EANS and WFNS

- Instructional Training Course, Eurospine (Spine Society of Europe)

- Fellowship Training Programme, Eurospine (Spine Society of Europe)

- Research and development officer, British Cervical Spine Society

- Scientific Programme Committee Eurospine (Spine Society of Europe)

- Scientific Programme Committee, World Federation Neurological Societies

- Advisor, Computer Assisted Orthopaedic Surgery Scientific

- Regional Oncology Task Force Spinal Malignancy, report, Department of Health, UK

- National Infection Advisory Committee Neurosurgery, report, Department of Health, UK

- Research Fellowship Advisory Board, Royal College of Surgeons (UK)

- Royal College of Surgeons (UK) Working Party on Image Guided Surgery

- Council member, Society British Neurological Surgeons